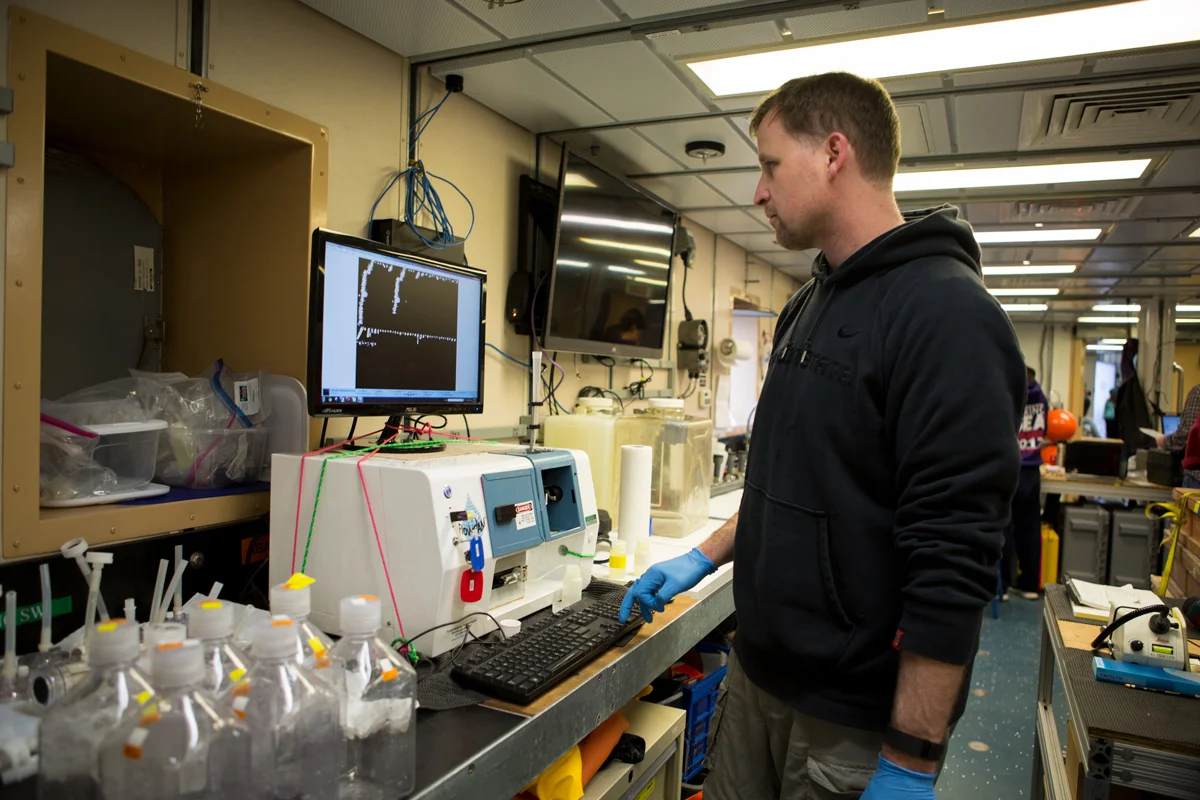

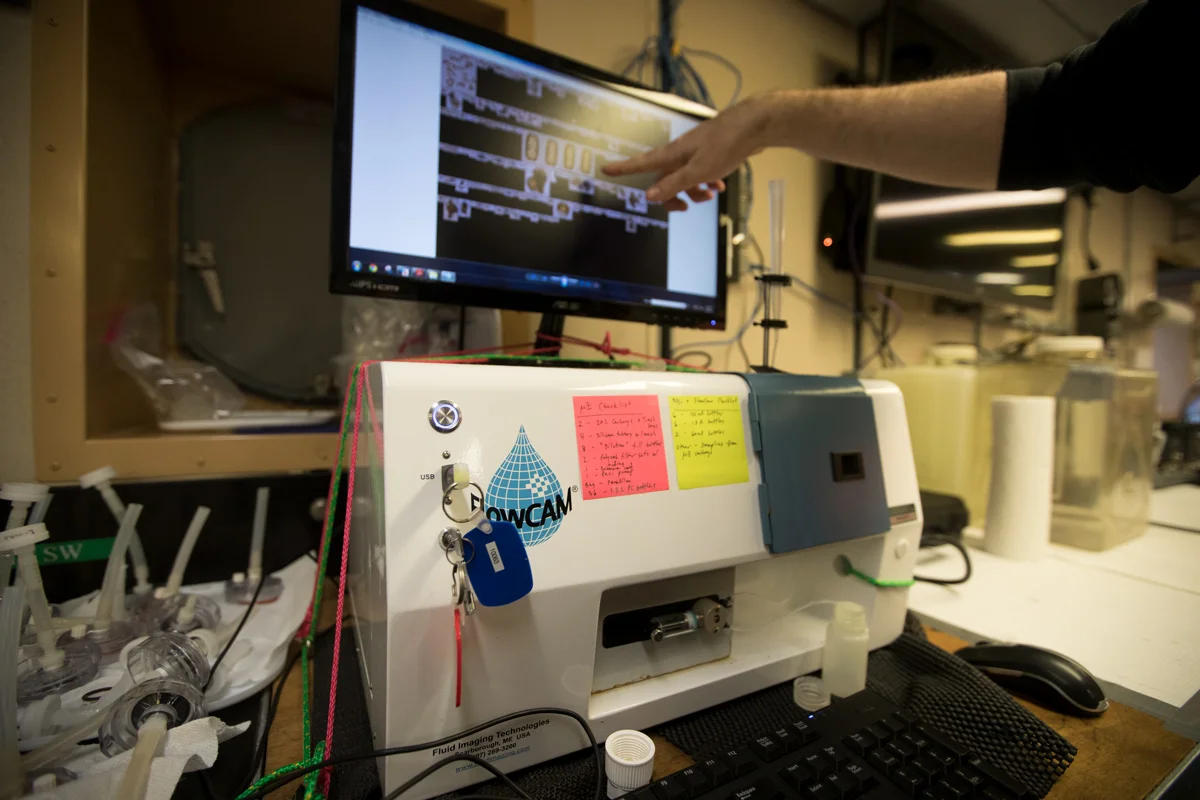

Scientist Jeff Krause describing the process of filtration through the FloCam instrument, an incredible tool used to visualize even the smallest of microplankton in the water column. Photo credit: Brendan Smith

The first time I saw plankton under a microscope was in 10th grade. My instructor brought a plankton net into class, which he used that morning. When peering into the eye piece, I saw a miniature aquatic ecosystem. Instead of grasses and shrubs, there were diatoms —a single cell plant plankton, i.e., phytoplankton, with a distinctive glass shell. Instead of cows or sheep grazing on grass, diatoms were being consumed by copepods (an animal plankton, or zooplankton). Instead of insects munching on grass blades, there were ciliates (single-cell zooplankton, which are much smaller than copepods) grazing on phytoplankton. Some moments in life have immediate impact, but how could I have known that 20 years ago, that the little ecosystem which caught my gaze would be the beginning of a career path which brought me here?

Fast forward to 2017, my friend and colleague, Mike Lomas (Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences) and I are aboard the R/V Sikuliaq conducting experiments to test hypotheses we have been discussing for years in the Bering and Chukchi Seas. The main question driving our work: what is the fate of all that organic matter produced by diatoms? Does it get consumed by large (e.g. copepods) or small (e.g. ciliates) zooplankton?

Such a broad question gets geeks like us excited, but why should any normal person care about this? Answer: phytoplankton, like diatoms, are the base of the regional food web, and a higher proportion of diatoms among phytoplankton is thought to correspond with more potential for fisheries. For instance, lots of diatoms fuel an efficient food web in the water column (e.g. to feed the zooplankton prey of pollock larvae) or they may sink to the benthos (e.g. providing food to shellfish and worms).

To do this work, Mike and I use various experimental approaches. We have designed, detailed, and replicated 16-hour experiments which take hours of effort on the front and back end to do successfully; these tell us how much daily phytoplankton growth is quickly consumed by microzooplankton. Mike is gathering samples for a high-speed instrument called a flow cytometer, to analyze the smallest plankton cells (those less than 0.005 millimeters in size!) in our experiments and understand their growth and grazing losses relative to diatoms. In separate experiments, I add an isotope to experimental water and follow it into diatoms’ glass shells, this conveys important information about their growth. I also brought my FlowCAM®, a high-speed microscope which not only allows you to view the microscopic organisms (e.g. diatoms, ciliates), but it takes pictures of each single cell and instantly measures over 30 parameters about the cell (e.g. length, width, volume, color intensity) … this is a tremendous amount of data. Mike and I already have data and are seeing incredible variation in phytoplankton growth, biomass, and the rate which microzooplankton are eating them across our station locations. At some stations, microzooplankton appear to be eating all the new material produced by phytoplankton!

With the ice in the Chukchi Sea retreating early this year, and this condition is predicted to be more frequent in the future, perhaps we are getting a sneak peek into the ecosystem of the future. On a seemingly mundane day in 1997, I got a glimpse into my future but didn’t recognize the moment (what teenager would?). If this is the case for our research cruise this month, am I going to be the trained scientist who recognizes potential changes, or the teenager who goes about their business without paying a second thought to the future?

Jeffrey Krause

Dauphin Island Sea Lab & University of South Alabama

In memory of my grandmother, Arlene O. Krause, rest in peace (April 1927 – June 2017)

Scientist Jeff Krause describing the process of filtration through the FloCam instrument, an incredible tool used to visualize even the smallest of microplankton in the water column.Photo credit: Brendan Smith