Portrait of Stephanie O'Daly by her lab station. Photo credit: Brendan Smith

“Where do you live?” This is one of the first questions people will ask you when you board a research vessel. This question is so common because researchers with different backgrounds and from different universities collaborate on projects, each bringing their own technicians and students. Crewmembers can live anywhere and when their turn comes around to go out to sea they will be flown to wherever the ship happens to be. What you end up with is a group of people who all live in different places coming together in isolation for the duration of the research cruise.

My answer to “Where do you live?” was simple up until May twenty-fourth when I, along with my cats, bike and two duffel bags, boarded a one-way flight from Raleigh/Durham, North Carolina to Fairbanks, Alaska. I’m a new graduate student at the University of Alaska at Fairbanks in the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences. Since arriving in Alaska I have many homes.

My home was in Fairbanks for five days. I had never been to Alaska before. Luckily, a friend of mine from college lives in Fairbanks and let me and my kitties crash with her. My stint in Fairbanks was short-lived and mostly consisted of filling out new student paperwork, looking for housing, and preparing for the upcoming research cruise.

After that I flew to Dutch Harbor with my advisor. This port on the island of Unalaska was my home for 4 days. It was here that I boarded the R/V Sikuliaq. We transited from Dutch Harbor to Nome, Alaska. We spent a few nights at port in Nome, where some of the crew switched out and the rest of the scientists boarded. I explored Nome, my new home, checking out its salty bars and sea glass-sprinkled beaches. Over the next two weeks we traveled from the Bering Sea through the Bering Strait and finally into the Chukchi Sea. I traveled nearly the entire western coast of Alaska and crossed into the Arctic Circle all while being an Alaskan resident for less than one month.

Stephanie climbing on the CTD rosette to get to some of the equipment for the UVP. Photo credit: Brendan Smith

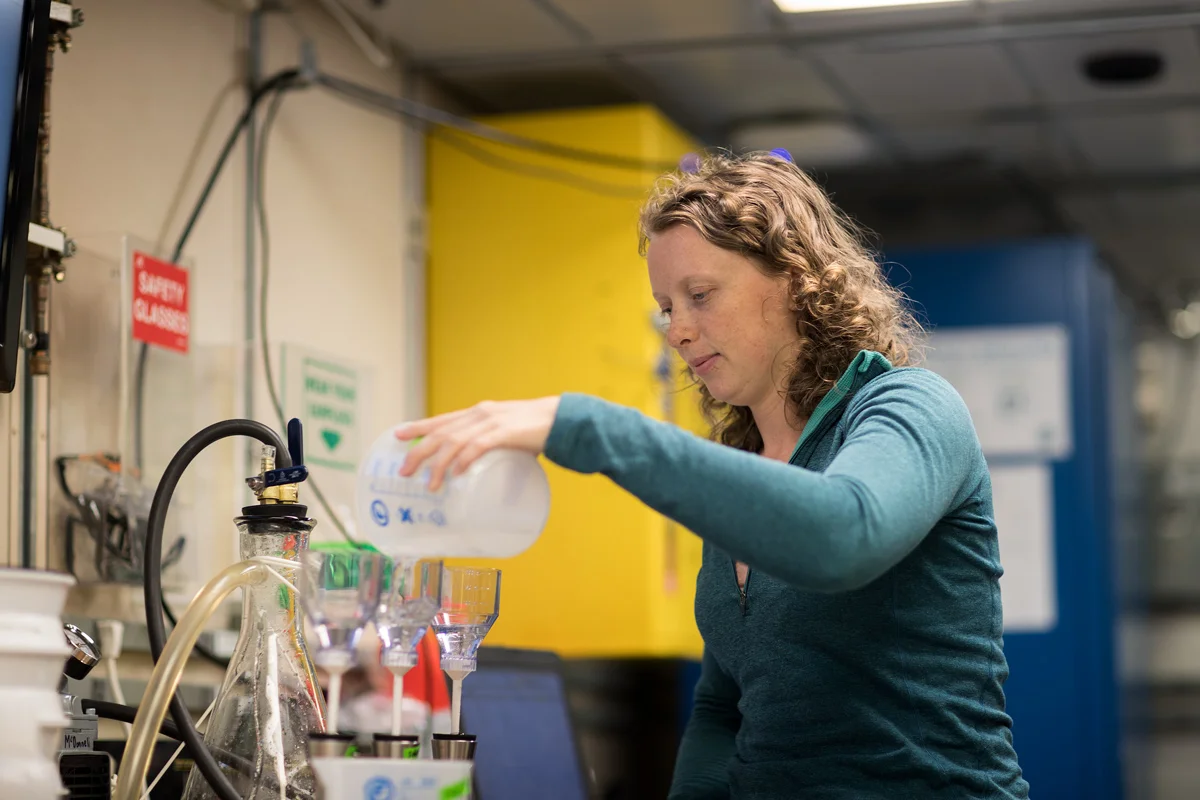

My role on the cruise is looking at particulate organic matter in the ocean. This can take the form of zooplankton (tiny animals), phytoplankton (tiny plants), bacteria, detritus (dead plants and animal waste), and aggregates (basically when any of the above breaks down and sticks together). Organic matter is anything that is made of carbon. When you look at the carbon cycle, the largest portion of carbon on earth is found in the sea floor. Carbon is introduced from the land into the ocean through river discharge. It is introduced from the atmosphere through a chemical exchange. It is introduced through plant growth in the ocean using energy from the sun. I’m studying what form organic matter takes and how that changes at different water depths, at different locations in the ocean, how it moves in the water, and its ultimate fate. We measure this using a few different methods. One is taking images of the water. We strapped a microscope camera (called an Underwater Vision Profiler) to the CTD rosette to take photos of zooplankton, larger phytoplankton, and other undissolved particles as it is lowered from the surface to the sea floor. We also use a laser in this same manner that measures scattering of the laser beam to determine particle size. We are filtering water collected at various depths to analyze carbon percentage makeup and total suspended particle matter weight. Using particle size and the results from the filter analysis we can determine what particles are made of. Finally, we will deploy two sediment traps, which will physically collect any particles falling to the seafloor in a given spot for a year. Next year we will collect these traps and analyze the particles collected.

Filtering water samples for suspended particulate matter. Photo credit: Brendan Smith

Hooking up the Underwater Vision Profiler (UVP) connectors. Photo credit: Brendan Smith

When people ask me where home is, I probably should say Fairbanks, but that doesn’t feel like home yet. I have spent over twice as much time on the Sikuliaq than I spent in Fairbanks. So I say that this ship is my home and it will be home for another week. While it is, I’m just another piece of organic matter floating in the ocean waiting to find a place where I may settle. And yes, I did see Russia from my house.